The transformation of iron into metal products such as tools for agriculture and other trades, weapons, locksmithery or nails represents an essential part of the Ripollès economy during the whole modern period down to the emergence of an industrial society in the 19th century.

The county saw iron ore mining develop, with deposits largely in the Ribes valley, as well as at Nyer and Mentet on the Conflent. Water infrastructures, such as channels, dams and ponds, were built on the banks of the rivers Ter, Freser, Rigat and Carboner and on the Forn torrent.

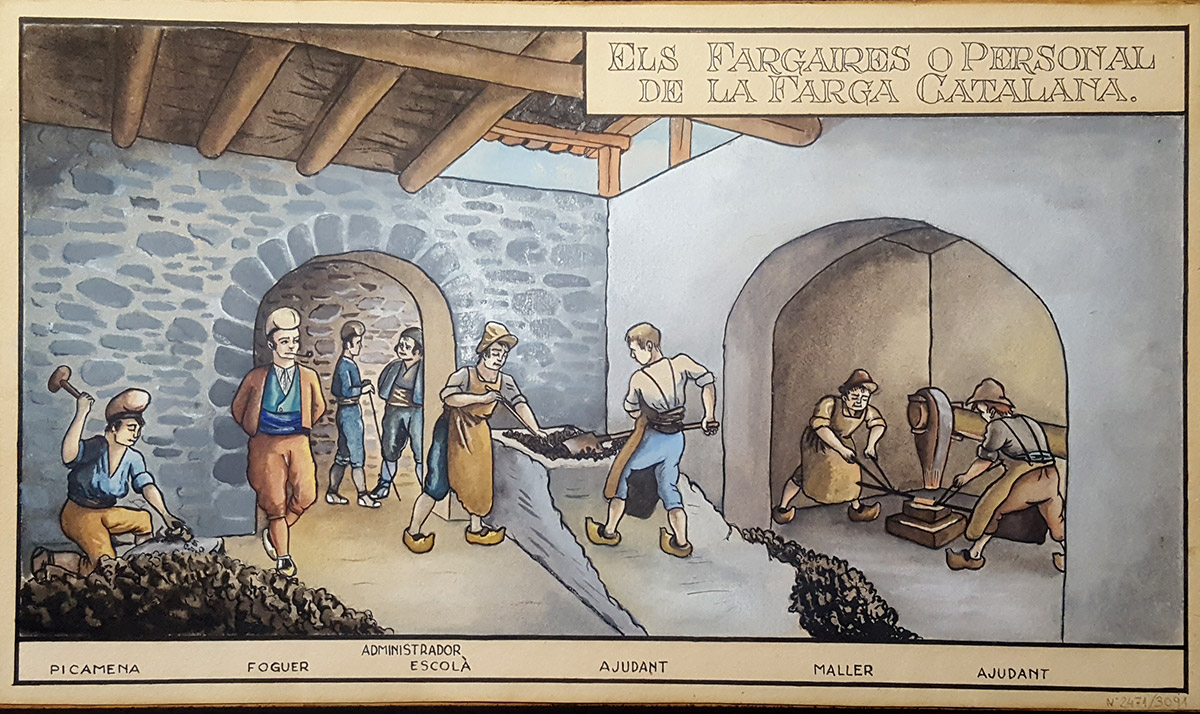

Entire woods were carbonised to supply the forges with charcoal, a fuel they needed to turn the iron ore into bloom – a pasty mixture which, once compacted with hammers, would become iron. These raw materials and energy sources fed the forges – establishments run by ironmasters with a deep knowledge of the secrets of their trade, working with other specialists whose jobs included making the fire, and heating the ore and hammering, stretching and heating the metal. Besides these, the iron-making process would need other specialists, such as miners with knowledge of how to exploit iron deposits, charcoal burners or carters.

Catalan Forge Hammer

From the Middle Ages to the 19th century, the countries of Western Europe – France, England, Austria and Italy among others – obtained iron using a metalworking method known throughout the world as the “Catalan procedure” or “Catalan forge”. The essential natural resources for operating them – that is iron ore, wood to make charcoal (for the furnaces) and water (used as a source of power) – could be found abundantly in this county where more than twenty forges are documented to the end of the 18th century.

The hammer was used in the old Catalan forge to compact the bloom, clean the slag out of it, and forge it. It was a device of very considerable dimensions that needed water power to activate it. It essentially consisted of a hammer that operated when force was applied to the end of the handle, which acted as a lever and raised the hammer head, allowing it to fall on top of the bloom placed on an anvil.

The nailmaker

The furnaces provided iron bars of the correct profile – the vergelina – which was heated red hot, cut, beaten and shaped in the small workshops of the nailmakers which, unlike blacksmiths’ shops, had a stump or a piece of wood into which the pieces needed to shape nails were fixed. These workshops, also called botigues, made more than a hundred types of them, of different sizes and types, supplying the demand of carpenters, shipbuilders and other trades. Each of them produced around 60,000 units a month. In the 18th century, the golden age of ironworking in the county, Ripoll had around a hundred establishments manufacturing nails and more than one hundred and fifty people making a living from this occupation. Groups of carters transported them to the ports of Barcelona, Canet and Tossa, and they also covered the markets of Catalonia,Aragon, Valencia, Murcia, Castile and Andalusia; they were even exported to Cuba. The importance of this industry meant that, from the 17th century onwards, nailmakers got together in their own guild, governed by strict rules, according to which, for example, a person could only achieve the status of master nailmaker and have his own workshop after serving a four-year apprenticeship and passing an examination set by the officials of the association.

This is a real botiga, from Campdevànol. Here we see a nailmaker, a fadrí (or worker) and an apprentice, operating the bellows.

Wrought Iron

Wrought iron was an indispensable material in preindustrial society. The blacksmith made agricultural tools – ploughshares, hoes, scythes, cartwheels – and tools for trades, such as hammers, files, saws, axes or picks, as well horseshoes and items for carts, mills or looms. Blacksmiths’ and locksmiths’ workshops made railings, locks, keys, grilles for windows and for cooking, toasting forks, pot hangers, traps and iron doors, with a great variety of shapes and decorative motifs, with which the craftsmen showed their mastery of the material and artistic abilities.

The Copper Forge

The iron forges disappeared in the 19th century, with the arrival of industrialisation, and only those that converted to work with copper remained active, as was the case with the Palau and Sant forges in Ripoll. These were establishments that continued to operate making use of the technical knowledge of the metal workers there, as the alterations to the facilities were minimal and were only visible in the hammer heads, which were narrower than that used for beating iron.

There was no copper mining in Ripollès as there had once been iron mining: however this new work continued to require coal for smelting and water power to activate the hammers and to obtain the air needed for the furnace. In this way, the traditional system characterising the old iron foundries was maintained.